“Visions” Project for 2022/23

We have an exciting new project to announce for the 2022/23 season. Visions combines the unmistakable, sepia-toned photographs of Edward Curtis choreographed to some truly timeless symphonic music by another notable humanist, Ralph Vaughan Williams. It’s a passion project that’s been on Nicholas’s plate for over three years, and we’re excited to finally offer this visual concerto for orchestras to program. Below is some background on Edward Curtis’s legacy and more about the new concert piece.

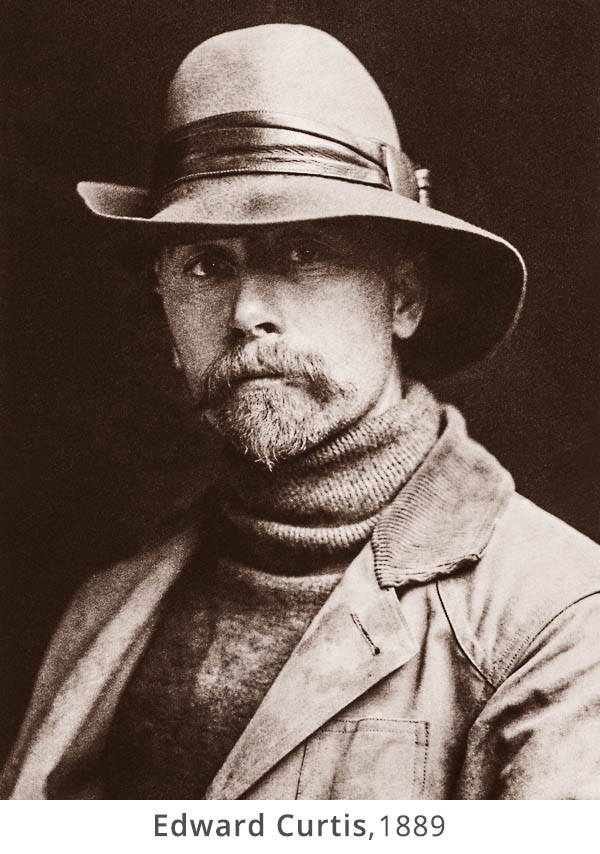

At the turn of the 20th Century, America was rapidly transforming. Technological changes were making the seemingly impossible possible, and the western expansion and “settlement” across the American frontier was well into its final stages. As a direct result, the diverse people who called that land home for centuries untold were being displaced and bearing unprecedented social and cultural changes. It was within this context that Edward Sheriff Curtis pursued his life’s work: photographing America’s First Peoples before, in his urgent view, their vibrant cultures, customs—and wisdom—were gone forever.

In 1900 Curtis began his journey in earnest after a fateful trip to see the Blackfoot tribe’s Sun Dance ceremony at the urging of early conservationist and national parks proponent George Bird Grinnell. Three decades later—through WWI, the Spanish Flu, and several personal setbacks—Curtis completed one of the largest ethnographic and artistic projects of all time. He made detailed drawings, took countless notes, produced film and sound recordings, published a glossary of 82 indigenous languages, and of course, created photographs—over 40,000 of them—with his large-format box camera, frequently developing the bulky glass plate negatives in his makeshift darkroom late into the night.

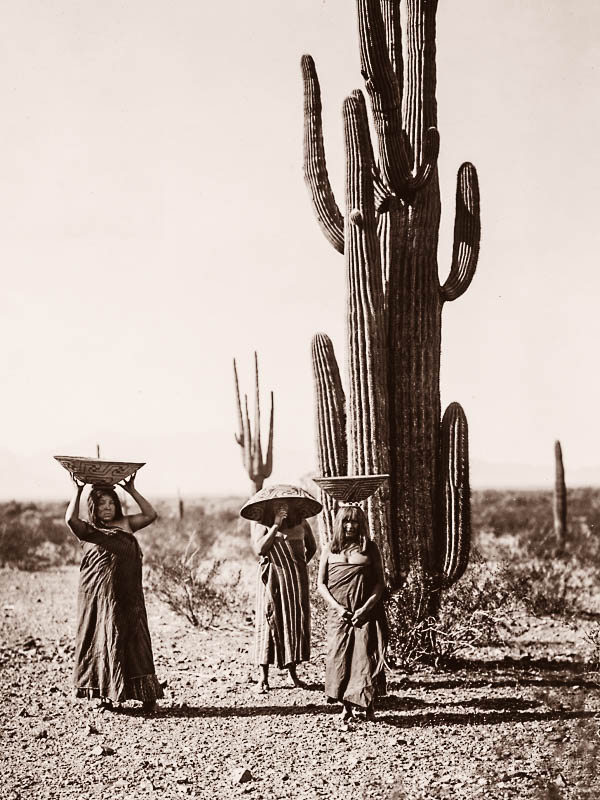

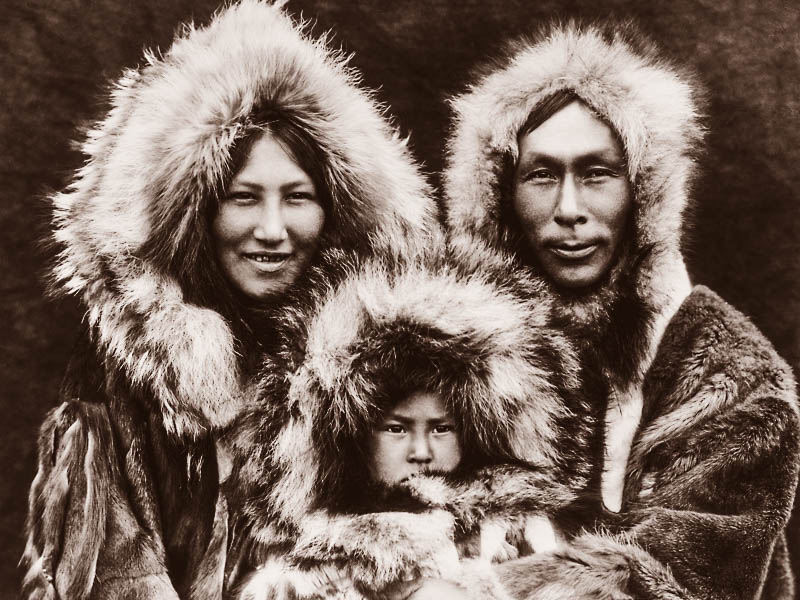

During this time Curtis visited (and often lived with) over 80 distinctive tribes spanning the U.S./Mexico border all the way up to northern Alaska, and it’s estimated that his all-consuming work involved the active participation of more than 10,000 native people. At times, Curtis even witnessed traditional practices and gatherings that had been outlawed by the federal government in this era of forced assimilation.

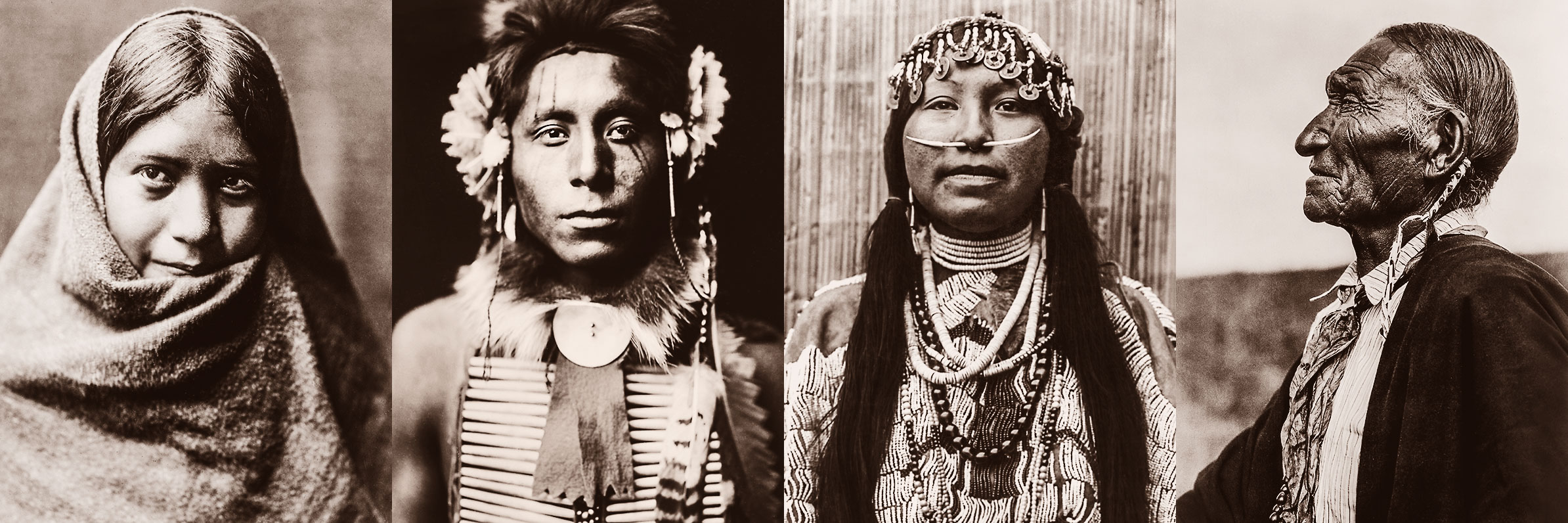

All of these efforts spilled into the 5,000 pages of Curtis’s monumental, 20-volume book series The North American Indian. When the first two volumes were released in 1907 and 1908, the New York Herald called it, “The most gigantic undertaking since the making of the King James Bible.” The 1,503 photographs that grace those pages are Curtis’s best known, and his enduring legacy. Some images, through countless museum exhibitions and subsequent books, are etched into our collective memories as being definitive of the American West and the “Native American experience.” In addition to his remarkably sensitive and skilled portraiture, Curtis photographed many facets of “indigenous life,” including: food gathering and preparation; modes of transport; settlements and architecture; wedding and funeral customs; community celebrations; masks, pottery and other artwork; and the sacred landscapes that served as both inspiration and guide for each unique lifeway.

“While primarily a photographer, I do not see or think photographically; hence the story of Indian life will not be told in microscopic detail, but rather will be presented as a broad and luminous picture.” — Edward Sheriff Curtis, 1905, Volume 1, page xv

Through a perceptive eye and an infinite curiosity, this self-taught American dreamer, with only a few years of schooling under his belt, created a lasting, and at times romanticized, tribute to a people who he cared deeply about. He was, in a sense, imagining what was, and what would never be again—and in doing so, finding his own place in the world. More than 100 years later, with the struggles of the Coronavirus pandemic, climate change, and the reenergized movement for racial equality, this same longing for a “simpler time,” our basic human connectivity to nature, and our striving for unity with one another is more important than ever.

“Taken as a whole, the work of Edward Curtis is a singular achievement. Never before have we seen the Indians of North America so close to the origins of their humanity, their sense of themselves in the world, their innate dignity and self-possession. These photographs comprehend more than an aboriginal culture, more than a prehistoric past — more, even, than a venture into a world of incomparable beauty and nobility. Curtis’s photographs comprehend indispensable images of every human being at every time in every place. In the focus upon the landscape of the continent and its indigenous people, a Curtis photograph becomes universal. Edward Curtis preserved for us the unmistakable evidence of our involvement in the universe.” — N. Scott Momaday (Kiowa), from Sacred Legacy: Edward S. Curtis and The North American Indian

Coincidentally, Edward Curtis was also keenly interested in music. During his time photographing and living alongside tribes, he and his team made over 10,000 wax cylinder recordings (like the CDs of our time) of native songs, prayers and chants, which he eventually had transcribed. These later served as inspiration for composer Henry F. Gilbert, who Curtis commissioned to write music for an ambitious theatrical production. “The Curtis Picture Musicale” toured major cities on both the East and West coasts from 1911 to 1913 and featured live music written by Gilbert and performed by a small orchestra. As Curtis envisioned, “it will open with the music, the house in darkness. … In the music we want to carry the mood of the whole, well knit together.”

These are the crossroads from which Westwater Arts’ latest concert piece, Visions, takes off. Our multimedia artist and photographer, Nicholas Bardonnay, set about personally curating Curtis’s impressive archive of images to be choreographed and performed live with orchestras once again across the country. This is by no means a repeat of what Curtis was trying to convey through his early-1900s production, but a new rendition seen through new artistic eyes in a new era—and told through the power of digital technology and the energy of the modern orchestra. In the concert hall, Curtis’s images will take on a whole new life with our massive 440-square-foot panoramic screen as their canvas.

In considering the best musical pairing for the visuals, Nicholas pored over dozens of works, and consulted with several orchestra colleagues. Finally, he realized that the music needed to have a universal quality that wasn’t as tied to a specific culture but possessed a more transcendent, “standalone” beauty. Enter Vaughan Williams’s timeless Five Variants of ‘Dives and Lazarus.’ “There’s a stoicism, innocence, beauty, melancholy, and passion—a whole range of emotions—in the music that just feel right for this subject matter. Never do I look at the literal meaning of any musical work but how it feels inside, and more importantly, what kind of emotional landscape it paints when paired with the imagery. There’s a really important and captivating story to tell here, and I’m so looking forward to sharing this with audiences next year,” says Nicholas of the new production.

There are several ways for orchestras to share this new concert experience with their audiences in 2022/23. Visions can be programmed independently alongside other thematic orchestral music. However, we recommend dovetailing it with one or more pieces from our existing repertoire to create additional meaning and interpretations on the American West, indigenous heritage, and the natural world. Concert pieces such as National Park Suite, Reflections of the Spirit, Grand Canyon Country, Pre~Columbia, and Pacifica will thoughtfully complement the themes explored in Visions. Orchestras may also want to consider partnering with a local tribe to be honorary guests or artistic participants in the concert—or perhaps through one of our Community Collaborations to create a contemporary look at local “tribal life” as seen through the eyes of tribal members themselves.

Read more about Visions, view additional sample imagery, and see a complete list of pairing ideas at the link below.